It’s invisible. The only way to know it’s there is by seeing, feeling, or hearing its effects. But the wind makes a big difference in the performance of a flight, particularly a longer flight.

It’s easy to think of wind in terms of the surface winds we feel outside. A light breeze might clock 5-10 mph, a good wind for flying kites might reach 15-20 mph, and anything 30 mph or more might blow your chihuahua away. Hidden from most people’s awareness are the winds far above the surface when jets fly – 20,000 feet up to maybe 45,000 feet. The winds aloft, as we call them, are often much stronger, ranging from 40-50 mph up to 120 mph or even higher. While they don’t stop an airline from flying, they can greatly affect flight times and fuel burn.

How the Wind Affects a Passenger

When you book a flight, you see a time for departure and arrival. It’s tempting, and somewhat reasonable, to view those times as a promise. However, it’s rare for a flight to depart and arrive exactly as scheduled. Obviously, some flights depart late for any number of reasons, but even an on-time departure might arrive at its destination early, right on schedule, or late. The winds aloft, especially on a flight over two hours long, are one of the main reasons.

When an airline publishes a schedule months in advance, the planners have no idea what the weather or winds will be doing on the day your flight departs. So they make an educated guess based on the typical times for similar flights in the past and the general pattern of the winds along that route. The average winds aloft are stronger during the winter and weaker during the summer. Also, the winds in the continental U.S. generally blow from west to east. So the schedule planners might plan your Vegas to Baltimore flight to take 4 hours 25 minutes in January when the tailwind is likely to be stronger versus 4 hours 40 minutes in July when the winds are weaker.

But remember – it’s only an estimate. What actually matters are the winds aloft on the day you fly, and they can vary quite a bit even from one day to the next.

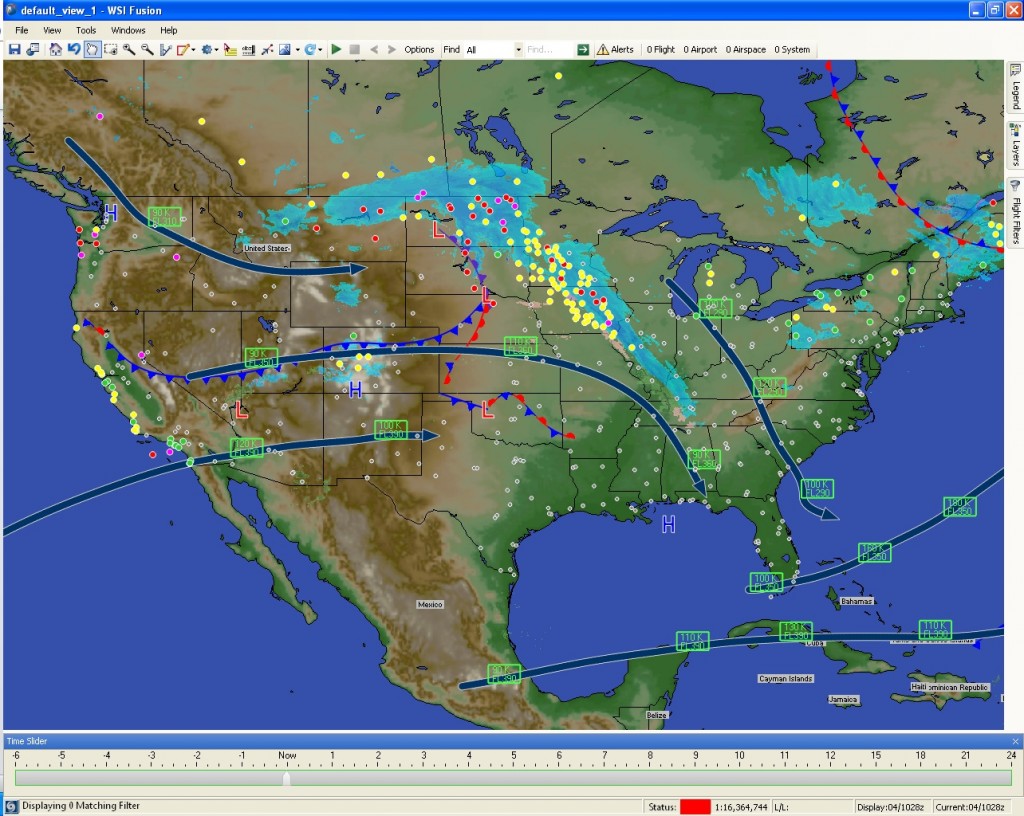

Here’s one example. This map shows yesterday’s weather and jetstream, the areas where the winds aloft are strongest. The dark blue lines with arrows indicate the jetstream. The winds are fairly consistent and strong from west to east until they reach the eastern states, when the turn southeast.

Thanks to the strong jetstream over the western and central US, one Vegas-Baltimore flight scheduled for 4h 25m only took 4h 12m, or 13 minutes less. Nice!

Here’s another map from today. Down south the winds are about the same, but the jetstream bends strangely from north to south over the Rockies.

What does this mean to our Vegas-Baltimore flight? Instead of getting a boost from a strong tailwind most of the way like yesterday, it gets a bit more of a crosswind over the middle of the country, meaning the plane can cover a bit less ground in a given amount of time with the same amount of effort. If you average out all the winds for the whole flight, today’s has about 22 mph less tailwind than yesterday’s. That makes today’s flight reach Baltimore about 8 minutes later than yesterday’s…still early by a few minutes, but not as early.

How I Can Help

When you drive somewhere, say from Dallas to Fort Worth, you have some options regarding your route. Maybe you like I-30, maybe you like I-20, or perhaps you prefer side streets. For an airline, routing works the same way to some degree, but not entirely. For most of our airports and flights, we have some flexibility regarding the path we take. However, to help air traffic controllers manage all the flights in the air, they generally prefer that we use certain routes that work well for them. We store those routes in our flight planning software and use them by default unless there’s some good reason not to.

Here’s where I come in.

On long flights such as Vegas-Baltimore or Orlando-Denver, I often run multiple versions of the flight plan. The first uses the preferred route. The second lets our flight planning software magically determine the ideal route using the current winds. Often, the preferred route is already ideal. But when the winds vary significantly in direction or speed from one part of the country to another, sometimes the ideal route (“best winds route,” in our jargon) is hundreds of miles north or south of the preferred route. If the custom route saves time and fuel over the preferred route, I can file it with air traffic control. As long as it doesn’t cause problems for their traffic flow, they usually let my flight use the route.

Here’s one example for an Atlanta-Vegas flight. The preferred route is white, the best winds route orange. Note how the best winds route stays north of the pref route to stay away from the jetstream. Sometimes the best winds route is longer than the pref route, but because its winds are better, the enroute time and fuel burn are lower.

Best winds routes take extra work and are not required. But unless I’m really busy and don’t have time, I give them a try on my long-haul desks. Why bother? They can save a lot of money.

Suppose I tweak the route on my Vegas-Baltimore flight to catch more of a tailwind. It might save 500 pounds of fuel and 6 minutes of flying time. That might not sound like much for a flight that’s burning 18,500 pounds of fuel. However, with jet fuel in Vegas costing $3.40/gallon, those 500 pounds translate into $253.73 in savings. In terms of net profit for the company, it’s like I convinced one more passenger to buy an advanced-purchase ticket. And it took maybe 3-4 minutes of extra work. No brainer, right? These make me seriously happy.

Sometimes I only save a couple hundred pounds, maybe $100 worth of fuel. In certain circumstances, I’ve saved $600-700 or more on a single flight. If I can plan several best winds routes in a shift, I can pay my salary for few days just in fuel savings. Those are some of the times I know I’m really making a difference at work.

The next time you fly somewhere, I suggest thinking about three things:

- Compare your actual departure and arrival times to the scheduled departure and arrival times. How much do they differ? Any ideas why?

- Even though it’s really hard to see their effect, look outside and think about how strong the winds are.

- Raise your glass to the flight dispatcher sitting in a room back at airline headquarters who planned your route and fuel load and is monitoring your flight.

Disclaimer: All thoughts expressed here are solely my own and do not necessarily represent those of Southwest Airlines, its Employees, or its Board of Directors.